– Part 1 –

In healthcare, as in numerous other industries, lean management is gathering increasing momentum. In a 2013 article for the National Center for Biotechnology Information titled Lean Management—The Journey from Toyota to Healthcare (©2013 Teich and Faddoul), Sorin T. Teich, D.M.D., M.B.A., and Fady F. Faddoul, D.M.D., M.Sc. provided a comprehensive overview of what lean management is, and how its principles can be applied to the healthcare industry:

In healthcare, as in numerous other industries, lean management is gathering increasing momentum. In a 2013 article for the National Center for Biotechnology Information titled Lean Management—The Journey from Toyota to Healthcare (©2013 Teich and Faddoul), Sorin T. Teich, D.M.D., M.B.A., and Fady F. Faddoul, D.M.D., M.Sc. provided a comprehensive overview of what lean management is, and how its principles can be applied to the healthcare industry:

History of the Lean Management Concept

The evolution of production systems is tightly linked to the story of Toyota Motor Company (TMC) that has its roots around 1918 when Sakichi Toyoda, who held a patent for an automatic loom that revolutionized the weaving industry, established his business. After selling the patents in 1929, the company reinvented itself in the automotive industry that, at the time, was dominated in Japan by local subsidiaries of Ford and General Motors (GM). Truck and car production began in 1935, and in 1937 TMC was formally incorporated.

By 1950, the entire Japanese auto industry was producing an annual output equivalent to three days of the US car production; it was around this time when Eiji Toyoda was sent to the US to study manufacturing methods. Another valued TMC employee, Taiichi Ohno, who joined the company in 1943, joined the visit and reasoned that the Western production systems had two major flaws:

- Producing components in large batches resulted in large inventories, and

- The methods preferred large production over customer preferences

Little by little, through much iteration, the Toyota Production System (TPS) evolved and provided a tool that used innovation and common knowledge, and that functioned well in an environment with different cultural values compared with the Western hemisphere. Only in 1965, when the system was rolled also to TMC’s suppliers, TPS began to be documented, and it was largely unnoticed until 1973 when the oil crisis affected the global automotive industry.

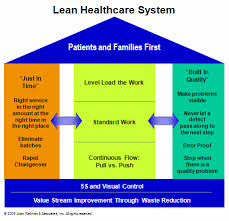

The performance gaps between Toyota and other car-makers were highlighted in 1990 in the book The Machine that Changed the World, in which the term “lean” production was coined. The exploration of the Toyota model led the authors to postulate the “transference” thesis that sustained the concept that manufacturing problems and technologies are universal problems faced by management, and that these concepts can be emulated in non-Japanese enterprises. In the next few years, the process of “extension” was accelerated by reports of Western companies in diverse sectors, incorporating lean principles that involved:

- Identification of customer value

- Management of “value stream”

- Developing capabilities of flow production

- Use of “pull” mechanisms to support flow of materials at constrained operations

- Pursuit of perfection through reducing to zero all forms of “waste”

Customer value identification was crucial in moving away from a production floor focus towards an approach that sought to enhance this value by adding product/service features while eliminating wasteful activities. As such, value is related to customer requirements, and it will be the customer that ultimately determines what constitutes muda (waste in Japanese) and what does not.

Lean is a multi-faceted concept and requires organizations to exert effort along several dimensions simultaneously; some consider a successful implementation achieving major strategic components of lean, implementing practices to support operational aspects, and providing evidence that the improvements are sustainable in the long term.

Clearly, this ambitious approach requires deep commitment and is setting a bar that impacts the organization at all levels. The question is how one can assess if a company is ready for such a drastic change and what it would take in order to ensure a successful transformative process; it is probably easier to provide an answer to the following complementary question: What are the main reasons for failures in companies that tried to implement a lean culture? These were identified as lack of senior commitment, lack of team autonomy, lack of organizational communications, organizational inertia, and lack of interest in lean. Another major factor is that lean provides principles for theoretical efficiency that implies more production with a smaller work-force; therefore workers may fear for their jobs.

End of Part 1

This concludes Part 1 of the 4-part series, Lean Management for Healthcare Organizations. If you’d like to learn more about lean management and how it can benefit your organization, contact the experts at BHM Healthcare Solutions today.

Email: results@bhmpc.com

Phone: 1-888-831-1171

or click on the “request information” below