Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are a hot button topic in healthcare right now for several reasons. First and foremost, since they are still the new kid on the block, there are some misunderstandings of just want constitutes an ACO and what the fundamental differences are from the former standard, HMOs. One of the primary focuses at the present time is establishing ACOs as being the go-to choice for patients (i.e. consumers) because it will allow them to broaden their access to healthcare services.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are a hot button topic in healthcare right now for several reasons. First and foremost, since they are still the new kid on the block, there are some misunderstandings of just want constitutes an ACO and what the fundamental differences are from the former standard, HMOs. One of the primary focuses at the present time is establishing ACOs as being the go-to choice for patients (i.e. consumers) because it will allow them to broaden their access to healthcare services.

Traditionally, in an HMO, a patient’s insurance coverage limits them to using only providers and services which are “in-network” with their insurance carrier. To seek care outside of the network of providers means more out-of-pocket payment is required of the patient. Access to care is therefore largely dictated by the insurance carrier, not the patient’s needs.

An ACO is assigned to a patient somewhat retroactively, meaning that it takes into consideration the patient’s medical history, the type of services that they predominantly utilized in a given year and where they are in location to the healthcare professionals whose services they sought out.

ACOs, then, make their money largely by examining population health and striving to increase it. They are rewarded for their efforts and successes through monetary incentives, which further the charge to make healthier communities and reduce unnecessary utilization of services.

Some people worry though that this means ACOs are so focused on population health that the initiatives that come from it reduce the focus on the individual patient. If the monetary incentive lies in creating and sustaining better population health, than those measures can’t be reasonably applied to individual patients – and probably not even patient groups.

This might ultimately be true. The common belief that currently dictates most decision making in healthcare is that things have become so dire that something has got to give. If changes aren’t made, even if they are imperfect, we will be looking at the next few decades as being nearly insurmountable in terms of healthcare access and fiscal difficulties.

Those who immediately criticism ACOs may be hoping for a definitive and comprehensive problem to the exhaustive problem of the current state of U.S. healthcare. The truth is, ACOs aren’t the solution, but they very well may be part of the solution. If anything, the chatter around the great HMO vs. ACO debate has brought some very important discussions to the forefront. Some major players in healthcare reform have tackled the big questions – the biggest being, how are we going to change?

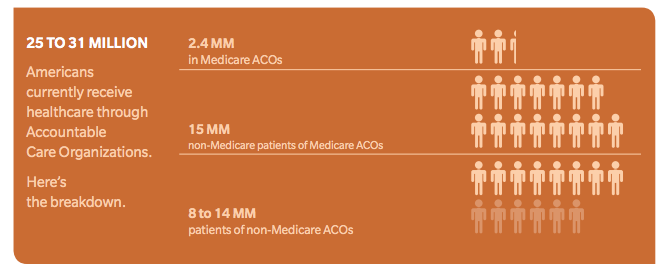

A study by Oliver Wyman reported that as of 2013, 25-31 million Americans are receiving care through an Accountable Care Organization – with more and more organizations applying for ACO status each quarter.

Another concern for most is the anticipated cost savings of ACOs. In the spirit of transparency in healthcare, the truth is, no one can say for sure what the cost savings will ultimately be for ACOs. The first part of the algorithm that will need to come together is the number of ACOs formed in the US and the extent to which they are effective. It’s too early to tell just how successful ACOs could be, but what we do know is that HMOs are passe, and they don’t work in our evolving healthcare landscape. The broader picture will be more than cost savings, but how will ACOs shape the healthcare reform, and our ability to develop sustainable, long-lasting changes.

test